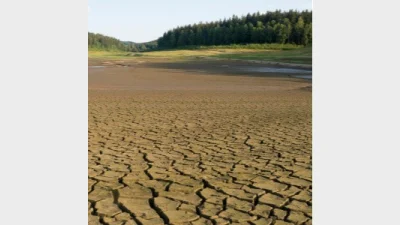

In times of drought

The current bushfire season has ravaged the east of Australia since June 2019 and has burned over 18 million hectares of land, paddocks, and homes.

The main cause, the drought, has impacted rural communities for years and many farmers are now going to financial advisers to save their businesses.

Hell Yes Financial Advice adviser, Vicki O’Connor, told Money Management the drought was going to cost the farming community a significant amount both financially and emotionally.

The community, she said, needed the help from advisers if Australia wanted to remain a country with its own farms and farmers on the land.

The style of farmers O’Connor worked with were very focused on building reserves to protect their business when drought and other natural disasters occurred.

“Some farmers have had previously profitable farm businesses that have allowed them to build up reserves and they have been using these to help them through,” she said.

These reserves included fodder stored for unexpected events, however O’Connor did not know anyone today with any fodder stores remaining, farm management deposits (FMDs) that she expected a reasonable outflow of funds to be occurring now, and off farm investments including superannuation.

O’Connor said many farmers had been running down their livestock and were not part of the farm management deposits scheme. If eligible, primary producers could set aside pre-tax income from their primary production activities during years of high income and that income could be drawn in future years as needed.

However, the Dubbo-based adviser said many farmers did not have the capability to put more or any into the FMD scheme and if they did, the interest was paid at a very low rate.

BANKING RESPONSE

As the scheme was managed by the banks, the banks were very nervous.

“At the moment they are in a pattern of wait and see but probably do not want to be seen as coming down on a farmer and saying that they have to sell,” O’Connor said.

“Banks are understandably very nervous and are already asking farmers for their drought recovery plan – how will they trade out of the additional debt that might be needed to allow them to trade out of the drought.

“In some cases, I am expecting that some farmers will simply be asked to sell their farms – that brings the challenge of who the buyers will be. Most farmers have plans around natural disasters. Any planner dealing with them would be looking at what needs to be done to protect the business.”

The Investment Collective’s managing director, David French, said the banks had been “pretty good” if they thought a farmer was organised and serious about running a farm as a business or property.

“They’ll work with you – they might make it interest only. There are also government initiatives where rural loan schemes that can be accessed that we’ve used such as replacing bank debt with a rural loan scheme debt at lower interest rates with more attractive capital repayment schedules,” he said.

While most farmers knew about the various government incentives they did not know how to access them. French noted that once the website was opened a professional was needed to navigate it.

For North West Wealth Management adviser James Smith, 90% of his clients have had to make changes or have discussions about their portfolios as a result of the drought to re-evaluate insurance premiums, superannuation contributions, or rearrange investments and income.

A few, he said, had to liquidate investments to keep afloat.

“It’s just the relentless nature of the drought going on and on. Normally there’s 18 months of it and then it rains but this time it’s been relentless and there’s no end in sight.

Mentally, it’s the hardest thing because they don’t know when it’s going to end,” he said.

While banks had been supportive, Smith said, the Royal Commission had made it harder to borrow money and this also added to farmers’ stress.

“It has become substantially harder to borrow and it is taking longer. There are many people in the same boat and the banks have to lend more money and figure out if people are viable going forward so it’s not necessarily the bank’s fault. There’s more i’s to dot and more t’s to cross,” he said.

On the insurance side, the Tamworth-based adviser said some of his clients were looking at restricting insurance as a lot could not afford premiums.

“Some insurers waived premiums and others might have deferred premiums and we help them put a letter together to move that forward. If they need money we look at whether they need to borrow more or cash-in investments, or they might take money out of super. It’s working through the options with them but sometimes they just want to talk to someone,” he said.

“Some of the farms had gone three years without income and if you think of it like an advice business or a retail shop most of them would not survive.

“The only way they have survived is by borrowing more money or cashing in investments. It’s a very different way of running a business when you have no income at all.”

SEPARATING BUSINESS FROM FAMILY

For French, one of the “big ticket items” financial advisers needed their farming clients to understand was that the farm was a business.

“It’s critical for the penny to drop that the farm is a business. They know they earn their living from it but they don’t see it as separate from their family. Their life is the farm and getting them over that bridge that this is a business and having to treat it as something separate and make decisions in the interest of the business is a big ticket thing,” he said.

Farmers were, French described, as proud small business people who did not engage with financial advisers until it was past a critical stage. Education played a big part in helping these clients engage with the banks.

“Once they understand that they could lose their whole livelihood and everything they stand for it resonates with them,” he said.

French said he would often travel to the farms and stay on the property, given the distance, which enabled him to acquire a deeper understanding of the business, the families, the underlying issues that his clients needed help with, and come up with solutions. On average French spent five visits for the best part of a week over a two-year period living in with the families.

French said he helped a family farm business that was not performing well and had difficult and unpleasant customers that were the most likely revenue source for the business which had put pressure on the relationship between the wife and husband.

After looking over the business operations and using economic modelling, he found a whole group of new customers that might be interested in their services. The family could rent out their farm to be used by disability support groups. This way, the business had steady income coming in from the national disability insurance scheme.

RURAL ADVICE

French stressed that spending time getting to know these types of clients was one of the most important aspects in the adviser/client relationship. This helped understand the situation, gave time to listen to their concerns, and the ability to be clear headed enough to step away and make a strategy.

“Because there isn’t a perception that there’s a difference between the business and the family, advisers need to be clear headed enough to draw the distinction out in their minds,” the Rockhampton adviser said.

“It’s all about numbers and saving the business which are two separate things so advisers can’t be too emotionally attached to the family drama. You need the guts to say they need to sell if that is necessary.”

Morvest Financial Planning adviser, Mark Carroll, said advisers working in these situations needed to be realistic on the returns they could achieve and that looking and income and cashflow was at the forefront.

“Returns are likely to be lower than what they had been used to five to 10 years ago. They don’t want to chew through their capital so it’s about managing spending, budgeting and cashflow. It’s all around income producing Australian equities, real estate, infrastructure assets, global equities that have an income skew,” the Moree-based planner said.

“They also may need to go up the risk profile and add more growth assets because farmers including retiree farmers tend to be more conservative in nature and tend to have a defensive portfolio. We’ve had to educate them to moving to a more growth orientated portfolio to get greater cashflow.”

Smith agreed that cashflow was important but stressed that advisers needed to appreciate the difference in cashflow management and the operation of their business.

“Having an appreciation that it is different. I talk to clients who have town businesses and clients that have been affected by the drought or fires and it’s having an appreciation of those differences,” he said.

Typically, these clients did not have pay as you go income and advisers need to need to understand different ways that their financial position is put together. They also tended to have more complex structures such as trust companies or super funds that owned some land.

“No doubt it has been a difficult time and while farmers have been the worst affected, there is a flow on effect into the towns from restaurants to accountants, to advisers, to butchers,” Smith noted.

“Everyone is impacted by the downturn and it has been going on for years and it will not change overnight. Even if there is rain now there will be no income for the next year or two and a lot of small businesses may never recover from this long sustained downturn period,” he said.

MENTAL HEALTH

The other invisible impact of the drought has been the emotional toll it has taken on rural community members’ mental health.

Smith said he completed a mental health first aid course to help recognise if clients were struggling mentally and to put them into contact with professionals who could help.

“When we do an insurance application 80% of our applications would have a mental health exclusion because they’ve been to someone and have gotten help or medication.

“80% of farmers tick the box that say they’ve had mental health issues and this is a much higher rate than the general public.”

Carroll said it was important for advisers to pick up on client attitude and demand changes, and if their clients did not appear like they used to be.

“You generally have a closer relationship with clients than other professions so while it is a hard topic it would be easier for an adviser to address. It’s not easy but it has to be done,” he said.

O’Connor said the problem was often that the farmers saw themselves as “guardians of the land” for the next generation and when there was a prolonged downturn they felt like they had failed their family and the land.

“I would probably put it up there with something like post traumatic stress syndrome (PTSD). When the drought does end they will find it hard to manage the impact of the return to the previous position. I would think this would leave a mark on many of them for years to come,” she said.

“If they’re going now into an era where it does rain farmers are then dealing with ‘where I get the money from, will the bank lend to me and what does my drought recovery plan look like?’

“For a lot of farmers that’s very hard when you’re already feeling depressed because it’s hard to lift your head to look that much further ahead. People think rain brings an end to it but it doesn’t, it brings a whole new series of challenges for the farmer.”

For French, being put in a position to advise a client to seek help from a psychologist or a GP is nothing new having done this several times.

“There are all these internal conflicts these farmers are dealing with and using an independent adviser as a sounding board is critical. I speak sternly to them and say they need help if I feel like their mental health has declined,” he said.

“Mental health thing is critical for people under financial pressure. People need a trusted conduit so that they can get their feelings out and understand what is going on and an adviser should immediately say ‘we need to get you help’ and probably the first step is going to a GP or a psychologist.”

Recommended for you

Marking off its first year of operation, Perth-based advice firm Leeuwin Wealth is now looking to strengthen its position in the WA market, targeting organic growth and a strong regional presence.

In the latest edition of Ahead of the Curve in partnership with MFS Investment Management, senior managing director Benoit Anne explores the benefits of adding global bonds to a portfolio.

While M&A has ramped up nationwide, three advice heads have explored Western Australia’s emergence as a region of interest among medium-sized firms vying for growth opportunities in an increasingly competitive market.

Private wealth firm Escala Partners is seeking to become a leading player in the Australian advice landscape, helped by backing from US player Focus Financial.