Private equity represents a vital cog in any economy, fueling much of the growth and innovation and helping entrepreneurs build such companies as Google, Apple and Tesla.

In addition to providing capital to startups, at the other end of the spectrum are buyouts, where private equity firms take over and restructure troubled companies. Private equity funds can unlock considerable value in private companies which potentially leads to strong investment returns.

Stages of private equity

Private equity represents a diverse group of investment types reflecting specific stages of business development including venture capital, growth equity, and buyouts.

Consider the lifecycle of a typical company. The business starts with an idea for a product or service. Initially the business idea may be funded by the founder’s own capital, and/or friends and family. This will typically drive the company’s initial launch and early growth. At this stage, founders will often turn to venture capital to further fuel growth.

Venture capital firms may invest when a company is not yet profitable and, often, before a company is generating meaningful revenues. Hence, this is typically the riskiest form of venture capital investing, particularly in an early-stage venture.

Growth equity funds, as the name suggests, will invest once a company has established a proven business model, has clients and is either profitable or has a clear path to profitability.

Lastly, at the other end of the spectrum are buyouts. This is where a private equity firm acquires a controlling stake in a company and then seeks to unlock value through a long-term plan. This represents the largest segment of private equity and can be further divided into leveraged buyouts and equity buyouts.

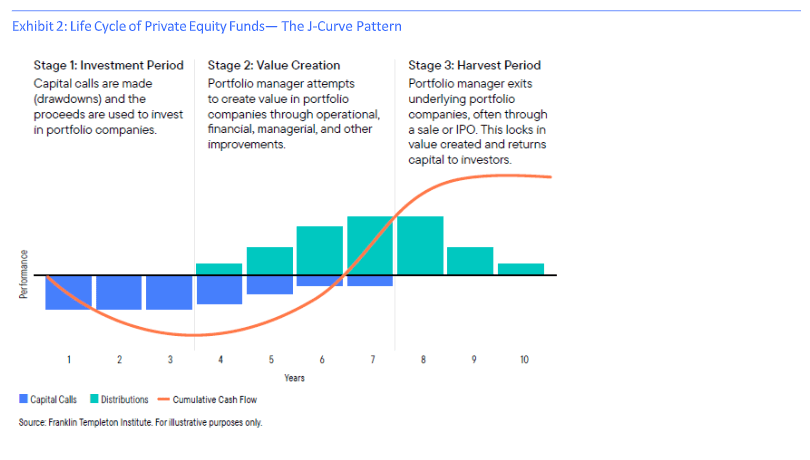

The J-curve

The “J-curve” is the term commonly used to describe the trajectory of a private equity fund’s cashflows and returns. An important liquidity implication of the J-curve is the need for investors to manage their own liquidity, to ensure they can meet capital calls on the front-end of the curve. During the initial investment period, capital is drawn down from investors by the fund manager to invest in portfolio companies. At this stage, investors are paying fees to the manager but will likely not see a markup in the underlying investments for some time.

In the second stage (value creation), those early investments made by the fund will start to generate a positive return, as the fund manager’s value creation measures play out. As investments start to return capital through the sale of portfolio companies, the overall return of capital will exceed the total amount of capital called down or invested. Investors will then start to realize positive cumulative cash flow, and these cashflows and returns will continue throughout the harvesting period as more companies are sold and fewer investments remain in the fund portfolio.

The appeal of private equity

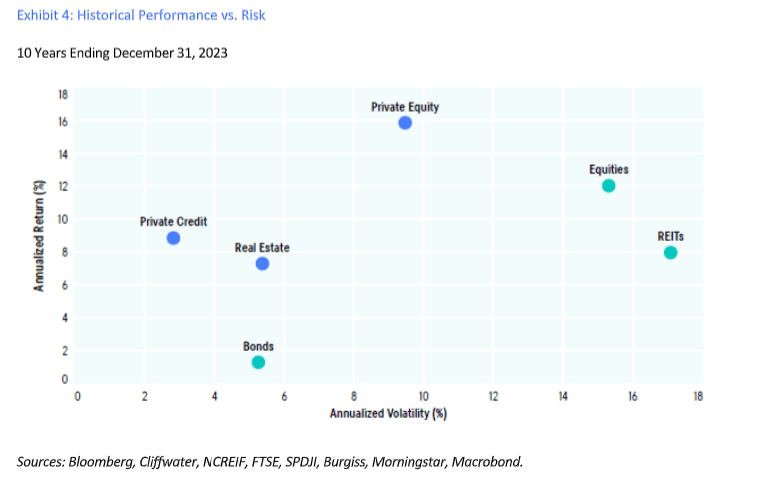

Part of the appeal of private equity has been its ability to historically deliver an illiquidity premium relative to public equities—the excess return for locking up capital for an extended period (7–12 years). Private equity in aggregate has delivered an illiquidity premium relative to its public market equivalents (S&P 500 and MSCI World Indexes) over multiple time periods. The magnitude of excess returns varies across market cycles.

The excess performance comes from a combination of factors. For starters, there is a growing universe of private equity opportunities, with over 17,000 US private companies with annual revenue of US$100 million or more, and a shrinking number of public companies (less than 3,700). The opportunities outside the United States—throughout Asia, Latin America and Europe—are equally impressive.

Private companies have also been staying private much longer due to their access to capital, so the private opportunity pool has been increasing, while the public market opportunity pool has been shrinking.

Private equity managers also benefit from a long-term perspective and an information advantage, focusing on creating value in their portfolio companies over a three-to-six-year period. They do not need to meet quarterly shareholders, and do not need to disclose strategic plans, new products in their pipelines or potential acquisitions.

As the data in Exhibit 4 illustrates, private equity has historically delivered attractive risk-adjusted returns relative to public markets.

Private equity managers can help companies unlock value in several ways, including meeting senior executives to develop and execute strategic plans to generate organic growth. Strategic growth initiatives can include expanding a company’s geographic footprint, developing new products or service lines, cross-selling products to existing customers and/or increasing marketing. Private equity managers will also frequently augment or upgrade a company’s existing leadership teams.

The democratisation of private equity

Institutions and family offices have historically used private markets to solve some of the challenges faced in today’s market environment—the need for attractive risk-adjusted returns, alternative sources of income, portfolio diversification and inflation hedging. Until recently, access to the private markets was more limited as most investors did not meet the eligibility requirements (qualified purchaser), and there were few products available to them. Over the last decade, access to private markets has dramatically improved.

In recent years, we have seen a growing demand for private markets by HNW investors, and a confluence of events has led to the growth of private market funds. The registered fund market has evolved to make these investments available to HNW investors, usually at lower minimums with more flexible liquidity options. While interval and tender-offer funds have been around for decades, it was not until after the global financial crisis (GFC) that these fund structures began to be used to access private markets. The growth of registered funds has also coincided with institutional-quality managers bringing new products to the market.

The secondary market

Given the recent environment of easy money and growing demand, private equity fund- raising grew rapidly over the last two decades. From 2011–2021, private equity generated 11 consecutive years of net distributions to limited partners. As such, institutions could typically count on distributions to offset commitments. However, private equity exits slowed dramatically in 2022 and 2023, causing many institutions to be overallocated.

Private equity valuations have reset from their lofty 2021 valuations. Higher interest rates and tighter credit conditions will likely put pressure on private equity valuations, and we believe investors may need to brace for a down round. Private equity fundraising is down substantially from its 2021 peak.

While private equity deals and exits have slowed, secondaries activity has picked up precipitously, as institutional investors seek to rebalance their portfolios. Many institutions committed significant capital to private equity in the last decade. The expectation was they would be rewarded in the form of an illiquidity premium—and they would begin to receive distributions as investments reached the harvest period.

As institutions found themselves overallocated to private equity, they sought to access the secondary market as a means to diversify their holdings and still meet future commitments. Secondary managers are able to select from broad pools of assets to acquire attractive investment interests at favorable pricing. Managers benefit from the significant inventory and the institutions’ need for liquidity.

The secondaries market has grown substantially over the last decade, from US$20 billion in 2006 to US$134 billion in 2021. As the market has matured, and institutions have struggled to find liquidity, secondaries managers have been able to select prized assets at a discount.

Secondary managers can be selective in deploying capital, and can diversify across stages of development (VC, growth equity, and buyout), geography, industry and vintage. By purchasing assets closer to their harvest stage, secondary managers may mitigate the effects of the J-curve, allowing investors to receive distributions sooner. Secondary managers may also avoid troubled assets and select prized assets.

Secondaries have become a vital cog in the growing private equity ecosystem, providing investors with access to liquidity, provide diversification and provide the broader ecosystem with additional scale during periods of stalled exits.

Conclusion

Private equity represents a growing part of the investable universe. It has long been used by institutions and family offices as a source of attractive risk-adjusted return potential and for diversification for their traditional portfolios.

Now, through product innovation and a willingness of institutional-quality managers to bring products to the wealth channel, private equity is more accessible to a broader group of investors, offering lower minimums and greater flexibility. Secondaries are providing liquidity to institutions that may be overallocated to private equity.

Tony Davidow is the senior alternatives investment strategist at the Franklin Templeton Institute.