Accommodative monetary policy in the US is set to continue, which should see the equity market climb higher, Mark Thomas writes.

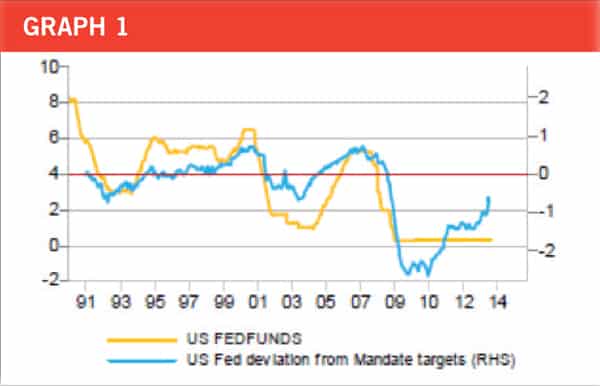

The US Federal Reserve has a dual mandate to achieve core inflation of two per cent and full employment, measured by an unemployment rate of 5.5 per cent.

However, despite being close to achieving these targets, Fed chair Janet Yellen has repeatedly said loose monetary policy is still required due to excess capacity in the US economy, as measured by the very low participation rate and high underemployment.

Therefore, there are conflicting signals and views related to US monetary policy and quantitative easing.

The Fed’s stated commitment to reach two per cent inflation and full employment appears to be rhetoric, with Yellen’s comments suggesting the Fed is focused on boosting inflation at any cost to erode the real value of the nation’s mounting debt pile.

The US government’s rising debt-to-GDP ratio could have serious implications for economic growth, especially if interest rates rise.

It seems increasingly likely that the Fed will maintain accommodative policy and keep rates low for longer. This could also extend the US equity market’s bull run, although it’s likely to be a bumpy ride higher.

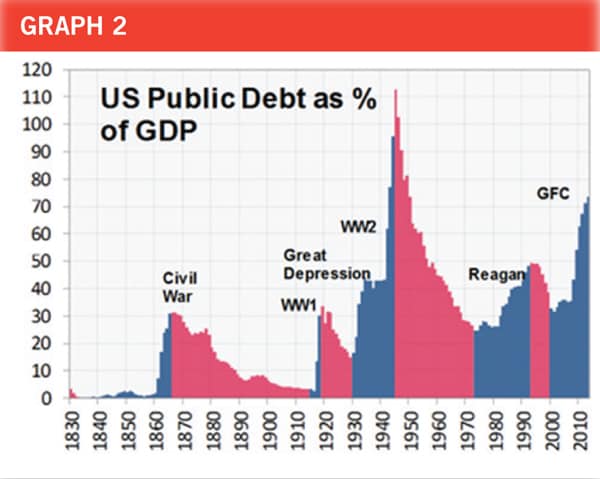

The US recorded a debt-to-GDP of 71.8 per cent in 2013, according to the CIA World Fact Book, or 101.53 per cent including external debt, according to the US Bureau of Public Debt. By comparison, US debt-to-GDP averaged 60.81 per cent from 1940 to 2013.

Debt-to-GDP measures the financial leverage of an economy. When interest rates are low, interest coverage costs are relatively low; however, in a rising interest rate environment, US growth could be slowed down for decades.

In order to achieve a healthy debt-to-GDP ratio of 30 per cent, accommodative US monetary policy needs to remain in place.

Yellen’s comments are inconsistent with the Fed’s own fundamental signal, which is illustrated in Graph 1.

It’s becoming clearer that the Fed wants to keep liquidity conditions accommodative until consumer spending and business investment kick in. To date these two parts of economic growth have been missing in the recovery despite very low long-term interest rates, improved household wealth and strong profits for US corporates.

The view is that the Fed is also concerned that any rise in interest rates will potentially undermine the recovery and reintroduce financial instability back into the US financial system.

Taking a broader, longer term view of the US economy, the US government has found itself in this position many times before. Debt blowouts are common throughout US history. The US government borrowed 40 per cent of GDP to pay for the Civil War but by 1915, it had almost paid back that debt. After World War I, the debt-to-GDP ratio rose to around 40 per cent again, and after World War II, it peaked at over 120 per cent.

The only realistic way out of debt is to grow nominal GDP faster than the total debt balance.

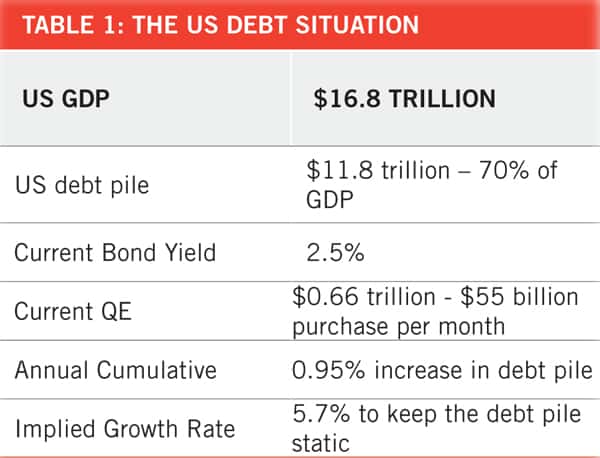

Currently the total debt balance for the US is roughly 70 per cent of GDP which, according to the World Bank, was $16.8 trillion in 2013. Simplistically with bond yields at 2.5 per cent US nominal GDP needs to grow at 1.8 per cent just to keep pace with the debt pile. However the debt pile is not static and is actually growing at a rate of QE purchases plus interest at the government bond yield rate. The US budget deficit contributes a further half a trillion dollars to the pile each year.

Table 1 attempts to break down the situation in a very simplified way.

This simple calculation suggests that nominal GDP needs to grow at 5.7 per cent per annum to keep the debt pile static if bond purchases remain at $55 billion per month and bond rates remain at 2.5 per cent.

Assuming that bond purchases go to zero and the US can manufacture nominal GDP growth of four per cent over 10 years, keeping bond yields at 2.5 per cent, it would take decades to return the debt-to-GDP ratio back to less than 10 per cent. This suggests that accommodative monetary policy/ QE will be here for much longer than most expect, possibly five to 10 years rather than three to five years. Consider that it took the US government 30 years to deleverage after WWII.

Mark Thomas is chief executive and chief investment officer of van Eyk Research.