China will bounce back

China may be going through a rough patch at present but the stock market capitalisation does not reflect its full economic potential. Hugh Young writes that demand for goods from a growing middle class is structural, not cyclical.

During these troubled times it's easy to forget why we liked Asia in the first place. This is a region of unprecedented wealth creation, a place that makes most of the things the world needs to buy, but where the scope of economic activity still isn't fully reflected in stock market capitalisation.

Economists have often said "when America sneezes, the world catches a cold", reflecting the importance of the US to the global economy.

But, in the last 12 months, for many investors around the world, China has replaced the Federal Reserve as their biggest concern. Is the country heading for a hard landing and how will that affect everyone else? What chance does Asia have if the region's biggest economy cannot get its act together?

The economy is slowing — that's not in dispute. Our latest forecast for gross domestic product (GDP) growth this year is 6.6 per cent, a far cry from China's double-digit expansion of yesteryear, and it may slow even further.

But is that really so bad? Slower growth is as much by design as by accident, as the economy moves away from an investment-led, export-driven model towards one in which domestic consumption plays the dominant role. The country wants growth that is sustainable.

China's latest stock market tumble was blamed on two things: a clumsy attempt to limit losses in an over-valued market that sparked panic selling; and poor communication around a loosening in renminbi policy that fuelled suspicions the country is seeking to devalue its way out of trouble.

That said, Chinese equity markets are divorced from reality. When share prices are driven by the interaction between state-sponsored market manipulation and the speculative instincts of millions of retail investors, they cease to serve as a gauge of a company's quality. Nor can they offer a glimpse into the health of an economy.

That's why the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges won't tell you that, while China needs to work through the effects of a massive misallocation of capital following the global financial crisis (GFC), the economy is nowhere near crashing.

Recent renminbi weakness — after a 26 per cent advance against the dollar since mid-2005 — is better understood within the context of ongoing currency liberalisation. Manufacturing weakness is partially offset by the growth of service industries, especially in the private sector.

Real estate, finance, hospitality, wholesale-retail, transport, construction and ‘other services' accounted for some 55 per cent of GDP in 2014, up from 47 per cent in 2006, according to data compiled by CLSA and Citic Securities. Their share will continue to rise, not only because industrial activity is shrinking, but because the contribution of the service sector may be under-reported.

Commodities not the biggest commodity

That's not to say China doesn't face considerable challenges — local government and corporate debt are big problems, the state sector is bloated and inefficient, while the property market remains fragile — but Beijing still has plenty of tools to avert catastrophe.

The country's slowdown has definitely been hard on commodity suppliers in the region such as Malaysia and Indonesia. Asian countries linked to China by production chains also suffer.

But the region has learned to diversify, economic activities have moved up the value chain, growing domestic consumption has reduced reliance on exports, and healthier government finances have pared vulnerabilities to external shocks. Reforms, despite many obstacles, are now priorities in many countries.

There's more good news. The Fed finally raised US interest rates late last year, in what is expected to be the first step on the long road towards monetary policy ‘normalisation', and the beginning of the end for an era of post-financial crisis market distortion.

The December rate-hike has removed one source of uncertainty for Asia. The focus will now be on the pace of subsequent increases. The initial signs suggest that the Fed intends to proceed with caution to avoid stifling economic recovery in the US.

Of course, while the US is tightening, both Japan and the European Union will probably receive more central bank stimulus. More money will almost certainly flow out of emerging markets and many Asian currencies will weaken against the dollar in the short-term. But if the Fed has judged the situation correctly, regional economies should benefit from a US-led pickup in demand.

There are also pockets of growth in Asia despite the tough conditions. For example, we have been keeping a close eye on selected companies operating within China's tourism, healthcare and insurance industries, while India's private sector banks continue to do well when measured against a range of performance indicators.

Elsewhere, some Asian companies are paying out more in dividends to their shareholders, while some (such as the Singapore property developers) have enhanced shareholder returns with share buybacks funded from deep cash reserves.

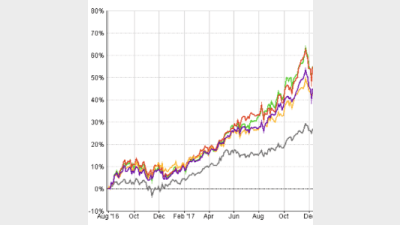

Investors will eventually be lured back to the region by compelling valuations. That's because Asian shares are cheap on both an historical and relative valuation basis, although there exists great variation between individual markets within the region.

During these troubled times it's easy to forget why we liked Asia in the first place. This is a region of unprecedented wealth creation, a place that makes most of the things the world needs to buy, but where the scope of economic activity still isn't fully reflected in stock market capitalisation.

The region's growing middle classes are driving demand for everything from white goods to financial products, from milk powder to washing powder. Unlike the financial markets, this demand is structural, not cyclical.

The Asian region will grow faster than the developed world for many years to come. So if investors are trying to anticipate what will happen over the next five years versus what has happened over the past five, the balance of risk must surely be shifting away from the developed markets again.

Our contrarian instincts tell us that volatility and opportunity go hand-in-hand. That's why our fund managers are starting to get excited again. Those of us who have been around a while have seen this all before and we know that Asia will pull through to emerge even stronger.

Hugh Young is the managing director of Aberdeen Asset Management Asia.

Recommended for you

Marking off its first year of operation, Perth-based advice firm Leeuwin Wealth is now looking to strengthen its position in the WA market, targeting organic growth and a strong regional presence.

In the latest edition of Ahead of the Curve in partnership with MFS Investment Management, senior managing director Benoit Anne explores the benefits of adding global bonds to a portfolio.

While M&A has ramped up nationwide, three advice heads have explored Western Australia’s emergence as a region of interest among medium-sized firms vying for growth opportunities in an increasingly competitive market.

Private wealth firm Escala Partners is seeking to become a leading player in the Australian advice landscape, helped by backing from US player Focus Financial.